I have had a lot of questions on the details of my treatment, what is it like to go through (aggressive) cancer treatment? I have avoided it until now, but here goes. My conclusions are in the last two paragraphs if details are not your thing, I won't be offended if you skip ahead. The biochemotherapy was very complex so that would be too difficult to explain, so I'll take you through a course of high-dose IL2 I received after my t-cell replacement. Join me on a not so pleasant cancer treatment journey, a week in the life if you will.

Jerry Seinfeld had a joke about how there is no normal strength pain medication any more? There is "extra strength" and "super strength" but nothing normal. His suggested solution to figuring out what strength he needed was to ask his doctor to figure out what would kill him and then "back off just a little bit." That is kind of like IL2 treatment for melanoma, because you can get up to 12 doses of the stuff but most people get 3-7 as best as I can assess. The question of how much they give you is much like Seinfeld's joke, and is surprisingly as much art as it is science.

So you start by checking into the hospital, which can be an adventure all on its own. At MD Anderson they like to start IL2 patients on Mondays and give the doses every eight hours; at 9am, 5pm and 1am. You always have this in the back of your head when checking in but you are most likely going to start at 9am the next day - but maybe earlier. It makes it hard to brace yourself for what is coming when you don't know

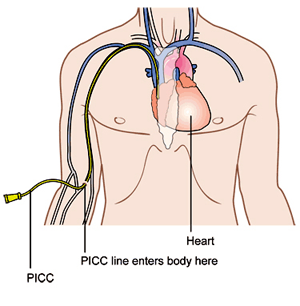

when it is coming. And there is the administrative nonsense, the paperwork, the overwhelming feeling of being a cancer patient when you walk into the massive building full of bald people toting around IV poles. You get into your room, unpack and make ready for whatever they throw at you. But first you must get connected to the machines so that you can become a bald person toting around an IV pole. There is the IV link to your PICC line (see diagram) that delivers the drugs directly to your heart. You usually keep the PICC line in between treatments, it's your semi-permanent plug-n-play that's stays with you most of the time you are in treatment. There is the cardio measurement which is five wires connected to tabs stuck on your chest. Then there is the oxygen monitor that is affixed to your finger. And then the blood pressure cuff on your arm. That is eight wires dangling off your body as you sleep, go to the bathroom, walk around the room, twenty four hours a day.

Your first dose at 9am so you start to brace yourself. By then you've met your nurse and assistant nurse, the floor nurse has probably stopped by and the doctors have made their daily rounds with you. They size you up to see what kind of week they will be having with you. You put up a strong face and try to act appreciative, like being friendly to the pilot on the airplane for no reason except that it seems like something that may help your situation. Then you wait, maybe an hour or five minutes or an hour and a half, until two nurses in biological warfare suits walk in with bags and bags of toxic, lifesaving drugs. For IL2 it takes 15 minutes for the drugs to flow into your system through your IV line. Then you watch the TV with one eye on the clock, the nurses and your caregiver in your room at the ready. They smile at you but you know they are also bracing for the storm of side effects that, in many ways, hurts them as much as you - especially if the caregiver is a parent or other loved one. My Gatorade made cold, hot blankets at quick access and the nurses armed with pre-approved multiples doses of demerol and dilaudid (both are opioids similar to morphine) - I'm ready as I can be. While my symptoms actually varied over my two courses of IL2, my first course had the same side effects after each dose. In these, at one hour, almost to the minute after the administration of the IL2, I would start to chill. Not Jimmy Buffet on a beach kind of chill, but as if someone tossed me naked into an ice bath. I'm talking the movie Titanic type cold that starts in your bones and works its way out. This takes hold in about half a minute and the hot blankets get piled on. The first injection of demerol helps give a feeling of warmth almost immediately but then the shakes start. The medical term is "hard rigors" and it is basically violent shaking from head to toe, in a kind of fetal position grabbing my knees and trying to control the outbursts from my own muscles. My bed shook so bad I swear it moved across the floor, my teeth chattered so hard I damaged my dental work and my heart beat so fast that I developed arrhythmias as I slept later that night. I could not talk during this, and I focused mainly on not hyperventilating which was about all I could do. This went on for one to two hours until the combination of successive and alternating opiate injections mollified my muscles enough to make them stop contracting and I fell off to half sleep. After each dose I felt like I had just completed a bike race, and with my heart rate averaging 165-190 bpm for an hour to two at a time that is the cardio equivalent of a fifty mile bike race for me - just a little harder effort.

So, in five hours you get to ask the question - do we do another dose or call it quits? The doctors assess the effects, they query you on how you feel, they see how much water your body has retained and how much fluid has gotten into your lungs (a side effect of IL2 is fluid leaking into other parts of your body). After my fourth treatment I was on oxygen full time. Part of my lung's lower lobes actually had collapsed which further complicated my breathing. Breathing is good, not breathing is not so good. The cardiologist had visited a few times and was on call for me. He put paddles permanently on my chest in case he needed to shock my heart during treatments. Really? It's late at night and the doctor called from home, the nurse said that he wanted to talk to me on the phone. He explained that this was a clinical trial - there are no "normal" results and that he could not say if my next dose would be easier or harder. He wanted to know if I could take another treatment, that he was going to green-light it medically but needed me to be on board. Gut-check time, DuPree. I said yes, one more. When the nurses brought in those toxic bags I started to regret my decision, honestly I did. But it was time to nut up or shut up, so I did it and then passed out to oblivion.

That was my fifth and last dose that course, but it is not over yet. The side effects of the treatment need to be addressed before you go home. That may take a day, or three or a week. You gain up to 20% of your body weight in extra fluids, your organs start to hiccup and they need to be coaxed back to normal function. Your skin may blotch and peel uncontrollably, turning an itchy fire red. Your digestive system protests and you get to discuss your bowel movements and urine output in great detail to any medical staff who comes in your room. And its 24 hours a day, every day, without break. Temperature and weight at 3am, blood draw at 4am, drugs at 5am, new nurse at 7am, around the clock. You can walk the floor to get out of the confines of your room but that does not free you too much. It is 302 steps to circumnavigate my floor of 32 rooms, plus or minus 6 steps. And so it goes, day after boring day, waiting for the magical word "discharge" to free you. Until you come back again for another treatment and start it all again. Next time may be easier, or it may be more difficult in a myriad of ways. Each treatment is different for each person, but it is rarely easy.

So this is what I mean when I say I'm fighting cancer. Cancer warriors do not check into a cancer treatment unit, hook up to an IV, sit back and hope for the best. No. They choose the aggressive treatment option over the standard treatment, they choose the clinical trial if they have to. They say "yes" when the doctors ask if they can take any more pain. They take control of their non-treatment time with exercise and diets. They research treatment options and choose their medical teams. They choose to sit up in their hospital beds instead of laying down, to walk with the IV pole instead of staying in bed whenever they can. They put on brave faces when sharing their cancer stories. They swallow the pain, the indignity, and the fear to be brave around another cancer warrior or care giver feeling down. They walk back into these hospital rooms over and over and over again. They start every day as I do, saying "I'm still alive - so fuck you cancer."

I guess I did not want to write this because I did not want cancer thinking we are having a tough time fighting. But you are right to ask me to share this. You have joined the fight against cancer if you are reading this, and I know that you can handle the truth. Just remember that in every fight - no matter how costly or how lengthy or how horrific - there is a victor. And cancer will not stand victorious after these battles. No way, no how.